The GRADE approach is a system for rating the quality of a body of evidence in systematic reviews and other evidence syntheses, such as health technology assessments, and guidelines and grading recommendations in health care. GRADE offers a transparent and structured process for developing and presenting evidence summaries and for carrying out the steps involved in developing recommendations. It can be used to develop clinical practice guidelines (CPG) and other health care recommendations (e.g. in public health, health policy and systems and coverage decisions).

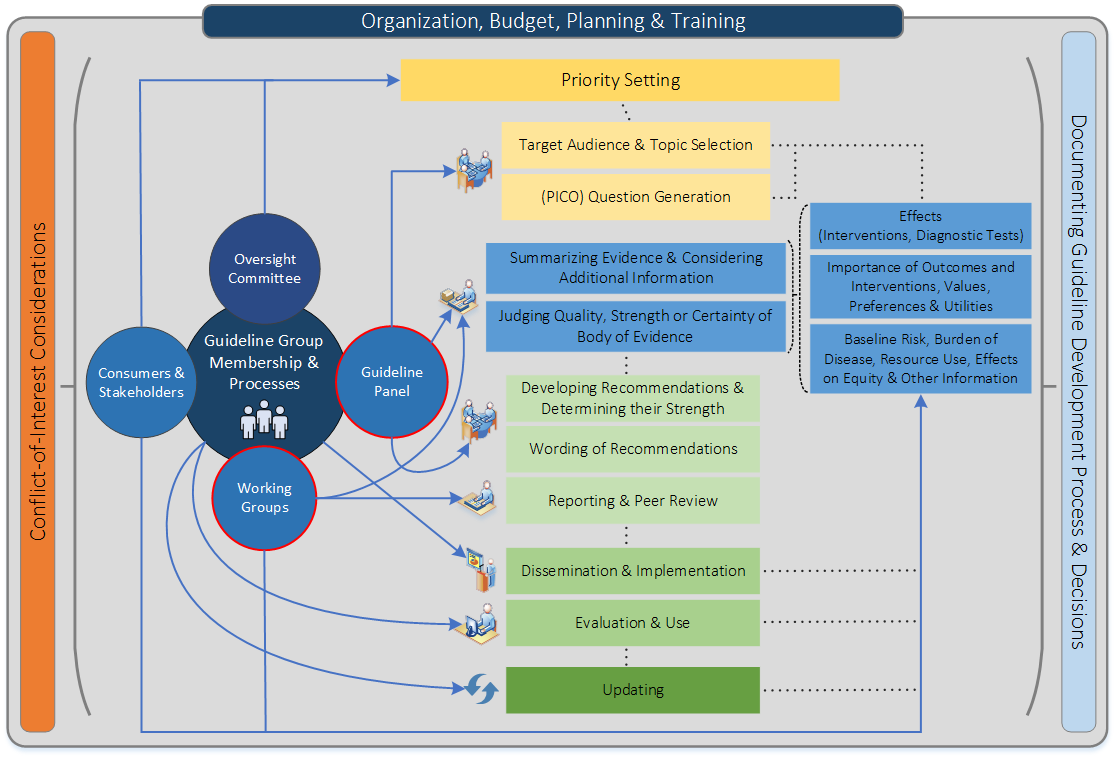

Figure 1 shows t he steps and involvement in a guideline development process (Schünemann H et al., CMAJ, 2013).

Steps and processes are interrelated and not necessarily sequential. The guideline panel and supporting groups (e.g. methodologist, health economist, systematic review team, secretariat for administrative support) work collaboratively, informed through consumer and stakeholder involvement. They typically report to an oversight committee or board overseeing the process. For example, while deciding how to involve stakeholders early for priority setting and topic selection, the guideline group must also consider how developing formal relationships with the stakeholders will enable effective dissemination and implementation to support uptake of the guideline. Furthermore, considerations for organization, planning and training encompass the entire guideline development project, and steps such as documenting the methodology used and decisions made, as well as considering conflict-of-interest occur throughout the entire process.

The system is designed for reviews and guidelines that examine alternative management strategies or interventions, which may include no intervention or current best management as well as multiple comparisons. GRADE has considered a wide range of clinical questions, including diagnosis, screening, prevention, and therapy. Guidance specific to applying the GRADE approach to questions about diagnosis is offered in Chapter The GRADE approach for diagnostic tests and strategies

GRADE provides a framework for specifying health care questions, choosing outcomes of interest and rating their importance, evaluating the available evidence, and bringing together the evidence with considerations of values and preferences of patients and society to arrive at recommendations. Furthermore, the system provides clinicians and patients with a guide to using those recommendations in clinical practice and policy makers with a guide to their use in health policy.

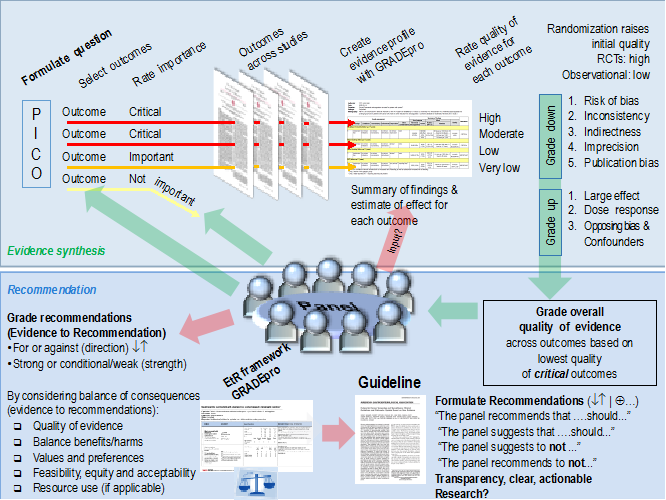

Application of the GRADE approach begins by defining the health care question in terms of the population of interest, the alternative management strategies (intervention and comparator), and all patient-important outcomes. As a specific step for guideline developers, the outcomes are rated according to their importance, as either critical or important but not critical. A systematic search is preformed to identify all relevant studies and data from the individual included studies is used to generate an estimate of the effect for each patient-important outcome as well as a measure of the uncertainty associated with that estimate (typically a confidence interval). The quality of evidence for each outcome across all the studies (i.e. the body of evidence for an outcome) is rated according to the factors outlined in the GRADE approach, including five factors that may lead to rating down the quality of evidence and three factors that may lead to rating up. Authors of systematic reviews complete the process up to this step, while guideline developers continue with the subsequent steps. Health care related related tests and strategies are considered interventions (or comparators) as utilizing a test inevitably has consequences that can be considered outcomes (see Chapter The GRADE approach for diagnostic tests and strategies).

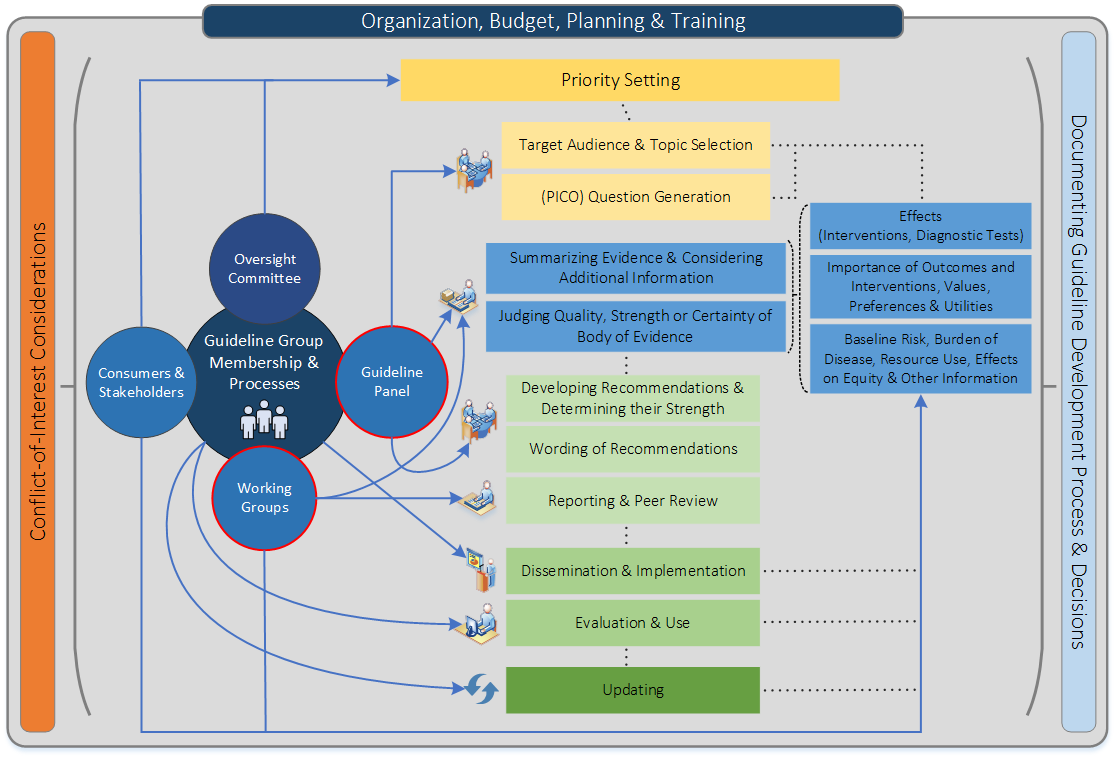

Next, guideline developers review all the information from the systematic search and, if needed, reassess and make a final decision about which outcomes are critical and which are important given the recommendations that they aim to formulate. The overall quality of evidence across all outcomes is assigned based on this assessment. Guideline developers then formulate the recommendation(s) and consider the direction (for or against) and grade the strength (strong or weak) of the recommendation(s) based on the criteria outlined in the GRADE approach. Figure 2 provides a schematic view of the GRADE approach.

Figure 2: A schematic view of the GRADE approach for synthesizing evidence and developing recommendations. The upper half describe steps in the process common to systematic reviews and making health care recommendations and the lower half describe steps that are specific to making recommendations (based on GRADE meeting, Edingburgh 2009).

For authors of systematic reviews:

Systematic reviews should provide a comprehensive summary of the evidence but they should typically not include health care recommendations. Therefore, use of the GRADE approach by systematic review authors terminates after rating the quality of evidence for outcomes and clearly presenting the results in an evidence table, i.e. an GRADE Evidence Profile or a Summary of Findings table. Those developing health care recommendations, e.g. a guideline panel, will have to complete the subsequent steps.

The following chapters will provide detailed guidance about the factors that influence the quality of evidence and strength of recommendations as well as instructions and examples for each step in the application of the GRADE approach. A detailed description of the GRADE approach for authors of systematic reviews and those making recommendations in health care is also available in a series of articles published in the Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. An additional overview of the GRADE approach as well as quality of evidence and strength of recommendations in guidelines is available in a previously published six-part series in the British Medical Journal. Briefer overviews have appeared in other journals, primarily with examples for relevant specialties. The articles are listed in Chapter 10. This handbook, however, as a resource that exists primarily in electronic format, will include GRADE’s innovations and be kept up to date as journal publications become outdated.

Clinical practice guidelines offer recommendations for the management of typical patients. These management decisions involve balancing the desirable and undesirable consequences of a given course of action. In order to help clinicians make evidence-based medical decisions, guideline developers often grade the strength of their recommendations and rate the quality of the evidence informing those recommendations.

Prior grading systems had many disadvantages including the lack of separation between the quality of evidence and strength of recommendation, the lack of transparency about judgments, and the lack of explicit acknowledgment of values and preferences underlying the recommendations. In addition, the existence of many, often scientifically outdated, grading systems has created confusion among guideline developers and end users.

The GRADE approach was developed to overcome these shortcomings of previous grading systems. Advantages of GRADE over other grading systems include:

Although the GRADE approach makes judgments about quality of evidence, that is confidence in the effect estimates, and strength of recommendations in a systematic and transparent manner, it does not eliminate the need for judgments. Thus, applying the GRADE approach does not minimize the importance of judgment or as suggesting that quality can always be objectively determined.

Although evidence suggests that these judgments, after appropriate methodological training, lead to reliable assessment of the quality of evidence (Mustafa R et al., Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 2013). There will be cases in which those making judgments will have legitimate disagreement about the interpretation of evidence. GRADE provides a framework guiding through the critical components of the assessment in a structured way. By allowing to make the judgments explicit rather than implicit it ensures transparency and a clear basis for discussion.

A number of criteria should be used when moving from evidence to recommendations (see Chapter on Going from evidence to recommendations). During that process, separate judgements are required for each of these criteria. In particular, separating judgements about the confidence in estimates or quality of evidence from judgements about the strength of recommendations is important as high confidence in effect estimates does not necessarily imply strong recommendations, and strong recommendations can result from low or even very low confidence in effect estimates (insert link to paradigmatic situations for when strong recommendations are justified in the context of low or very low confidence in effect estimates). Grading systems that fail to separate these judgements create confusion, while it is the defining feature of GRADE.

The GRADE approach stresses the necessity to consider the balance between desirable and undesirable consequences and acknowledge other factors, for example the values and preferences underlying the recommendations. As patients with varying values and preferences for outcomes and interventions will make different choices, guideline panels facing important variability in patient values and preferences are likely to offer a weak recommendation despite high quality evidence. Considering importance of outcomes and interventions, values, preferences and utilities includes integrating in the process of developing a recommendation, how those affected by its recommendations assess the possible consequences. These include patient and carer knowledge, attitudes, expectations, moral and ethical values, and beliefs; patient goals for life and health; prior experience with the intervention and the condition; symptom experience (for example breathlessness, pain, dyspnoea, weight loss); preferences for and importance of desirable and undesirable health outcomes; perceived impact of the condition or interventions on quality of life, well-being or satisfaction and interactions between the work of implementing the intervention, the intervention itself, and other contexts the patient may be experiencing; preferences for alternative courses of action; and preferences relating to communication content and styles, information and involvement in decision-making and care. This can be related to what in the economic literature is considered utilities. An intervention itself can be considered a consequence of a recommendation (e.g. the burden of taking a medication or undergoing surgery) and a level of importance or value is associated with that. Both the direction and the strength of a recommendation may be modified after taking into account the implications for resource utilization, equity, acceptability and feasibility of alternative management strategies.

Therefore, unlike many other grading systems, the GRADE approach emphasizes that weak also known as conditional recommendations in the face of high confidence in effect estimates of an intervention are common because of these factors other than the quality of evidence influencing the strength of a recommendation. For the same reason it allows for strong recommendations on the basis of low or very confidence in effect estimates.

Example 1: Weak recommendation based on high quality evidence

Several RCTs compared the use of combination chemotherapy and radiotherapy versus radiotherapy alone in unresectable, locally advanced non-small cell lung cancer (Stage IIIA). The overall quality of evidence for the body of evidence was rated high. Compared with radiotherapy alone, the combination of chemotherapy and radiotherapy reduces the risk of death corresponding to a mean gain in life expectancy of a few months, but increases harm and burden related to chemotherapy. Thus, considering the values and preferences patients would place on the small survival benefit in view of the harms and burdens, guideline panels may offer a weak recommendation despite the high quality of the available evidence (Schünemann et al. AJRCCM 2006).

Example 2: Weak recommendation based on high quality evidence

Patients who experience a first deep venous thrombosis with no obvious provoking factor must, after the first months of anticoagulation, decide whether to continue taking the anticoagulant warfarin long term. High quality randomized controlled trials show that continuing warfarin will decrease the risk of recurrent thrombosis but at the cost of increased risk of bleeding and inconvenience. Because patients with varying values and preferences will make different choices, guideline panels addressing whether patients should continue or terminate warfarin should, despite the high quality evidence, offer a weak recommendation.

Example 3: Strong recommendation based on low or very low quality evidence

The principle of administering appropriate antibiotics rapidly in the setting of severe infection or sepsis has not been tested against its alternative of no rush of delivering antibiotics in randomized controlled trials. Yet, guideline panels would be very likely to make a strong recommendation for the rapid use of antibiotics in this setting on the basis of available observational studies rated as low quality evidence because the benefits of antibiotic therapy clearly outweigh the downsides in most patients independent of the quality assessment (Schünemann et al. AJRCCM 2006)..

Those applying GRADE to questions about diagnostic tests, public health or health systems will face some special challenges. This handbook will address these challenges and undergo revisions when new developments prompt the GRADE working group to agree on changes to the approach. Moreover, there will be methodological advances and refinements in the future not only of innovations but also of the established concepts.

GRADE recommends against making modifications to the approach because the elements of the GRADE process are interlinked, because modifications may confuse some users of evidence summaries and guidelines, and because such changes compromise the goal of a single system with which clinicians, policy makers, and patients can become familiar. However, the literature on different approaches to applying GRADE is growing and are useful to determine when pragmatism is appropriate.

A guideline panel should define the scope of the guideline and the planned recommendations. Each recommendation should answer a focused and sensible health care question that leads to an action. Similarly, authors of systematic reviews should formulate focused health care question(s) that the review will answer. A systematic review may answer one or more health care questions, depending on the scope of the review.

The PICO framework presents a well accepted methodology for framing health care questions. It mandates carefully specifying four components:

A number of derivatives of this approach exist, for example adding a T for time or S for study design. These modifications are neither helpful nor necessary. The issue of time (e.g. duration of treatment, when an outcome should be assessed, etc) is covered in the elements by specifying the intervention(s) and outcome(s) appropriately (e.g. mortality at one year). In addition, the studies, and therefore the study design, that inform an answer are often not known when the question is asked. That is, observational studies may inform a question when randomized trials are no available or not associated with high confidence in the estimates. Thus, it is usually not sensible to define a study design beforehand. A guideline question often involves another specification: the setting in which the guideline will be implemented. For instance, guidelines intended for resource-rich environments will often be inapplicable to resource-poor environments. Even the setting, however, can be defined as part of the definition of the population (e.g. women in low income countries or man with myocardial infarction in a primary or rural health care setting).

Errors that are frequently made in formulating the health care question include failure to include all patient-important outcomes (e.g. adverse effects or toxicity), as well as failure to fully consider all relevant alternatives (this may be particularly problematic when guidelines target a global audience).

The most challenging decision in framing the question is how broadly the patients and intervention should be defined ( see Example 1 ). For the patients and interventions defined, the underlying biology should suggest that across the range of patients and interventions it is plausible that the magnitude of effect on the key outcomes is more or less the same. If that is not the case the review or guideline will generate misleading estimates for at least some subpopulations of patients and interventions. For instance, based on the information presented in Example 1, if antiplatelet agents differ in effectiveness in those with peripheral vascular disease vs. those with myocardial infarction, a single estimate across the range of patients and interventions will not well serve the decision-making needs of patients and clinicians. These subpopulations should, therefore, be defined separately.

Often, systematic reviews deal with the question of what breadth of population or intervention to choose by starting with a broad question but including a priori specification of subgroup effects that may explain any heterogeneity they find. The a priori hypotheses may relate to differences in patients, interventions, the choice of comparator, the outcome(s), or factors related to bias (e.g. high risk of bias studies yield different effects than low risk of bias studies).

Example 1: Deciding how to broadly to define the patients and intervention

Addressing the effects of antiplatelet agents on vascular disease, one might include only patients with transient ischemic attacks, those with ischemic attacks and strokes, or those with any vascular disease (cerebro-, cardio-, or peripheral vascular disease). The intervention might be a relatively narrow range of doses of aspirin, all doses of aspirin, or all antiplatelet agents.

Because the relative risk associated with an intervention vs. a specific comparator is usually similar across a wide variety of baseline risks, it is usually appropriate for systematic reviews to generate single pooled estimates (i.e. meta-analysis) of relative effects across a wide range of patient subgroups. Recommendations, however, may differ across subgroups of patients at different baseline risk of an outcome, despite there being a single relative risk that applies to all of them. For instance, the case for warfarin therapy, associated with both inconvenience and a higher risk of serious bleeding, is much stronger in atrial fibrillation patients at substantial vs. minimal risk of stroke. Thus, guideline panels must often define separate questions (and produce separate evidence summaries) for high- and low-risk patients, and patients in whom quality of evidence differs.

Another important challenge arises when there are multiple comparators to an intervention. Clarity in choice of the comparator makes for interpretable guidelines, and lack of clarity can cause confusion. Sometimes, the comparator is obvious, but when it is not guideline panels should specify the comparator explicitly. In particular, when multiple agents are involved, they should specify whether the recommendation is suggesting that all agents are equally recommended or that some agents are recommended over others ( see Example 1 ).

Example 1: Clarity with multiple comparators

When making recommendations for use of anticoagulants in patients with non-ST elevation acute coronary syndromes receiving conservative (non-invasive) management, fondaparinux, heparin, and enoxaparin may be the agents being considered. Moreover, the estimate of effect for each agent may come from evidence of varying quality (e.g. high quality evidence for heparin, low quality of evidence for fondaparinux). Therefore, it must be made clear whether the recommendations formulated by the guideline panel will be for use of these agents vs. not using any anticoagulants, or also whether they will indicate a preference for one agent over the others or a gradient of preference.

GRADE has begun to tackle the question of determining the confidence in estimates for prognosis. They are often important for guideline development. For example, addressing interventions that may influence the outcome of influenza or multiple sclerosis will require establishing the natural history of the conditions. This will involve specifying the population (influenza or new-onset multiple sclerosis) and the outcome (mortality or relapse rate and progression). Such questions of prognosis may be refined to include multiple predictors, such as age, gender, or severity. The answers to these questions will be an important background for formulating recommendations and interpreting the evidence about the effects of treatments. In particular, guideline developers need to decide whether the prognosis of patients in the community is similar to those studied in the trials and whether there are important prognostic subgroups that they should consider in making recommendations. Judgments if the evidence is direct enough in terms of baseline risk affect the rating about indirectness of evidence.

Defining a health care question includes specifying all outcomes of interest. Those developing recommendations whether or not to use a given intervention (therapeutic or diagnostic) have to consider all relevant outcomes simultaneously. The Guideline Development Tool allows the selection of two different formats for questions about management:

As well as one format for questions about diagnosis:

1. Should manual toothbrushes vs. powered toothbrushes be used for dental health?

2. Should topical nasal steroids be used in children with persistent allergic rhinitis?

3. Should oseltamivir versus no antiviral treatment be used to treat influenza?

4. Should troponin I followed by appropriate management strategies or troponin T followed by appropriate management strategies be used to manage acute myocardial infarction?

Given that recommendations cannot be made on the basis of information about single outcomes and decision-making always involves a balance between health benefits and harms. Authors of systematic reviews will make their reviews more useful by looking at a comprehensive range of outcomes that allow decision making in health care. Many, if not most, systematic reviews fail to address some key outcomes, particularly harms, associated with an intervention.

On the contrary, to make sensible recommendations guideline panels must consider all outcomes that are important or critical to patients for decision making. In addition, they may require consideration of outcomes that are important to others, including the use of resources paid for by third parties, equity considerations, impacts on those who care for patients, and public health impacts (e.g. the spread of infections or antibiotic resistance).

Guideline developers must base the choice of outcomes on what is important, not on what outcomes are measured and for which evidence is available. If evidence is lacking for an important outcome, this should be acknowledged, rather than ignoring the outcome. Because most systematic reviews do not summarize the evidence for all important outcomes, guideline panels must often either use multiple systematic reviews from different sources, conduct their own systematic reviews or update existing reviews.

Guideline developers must, and authors of systematic reviews are strongly encouraged to specify all potential patient-important outcomes as the first step in their endeavour. Guideline developers will also make a preliminary classification of the importance of the outcomes. GRADE specifies three categories of outcomes according to their importance for decision-making :

Critical and important outcomes will bear on guideline recommendations, the third will in most situations not. Ranking outcomes by their relative importance can help to focus attention on those outcomes that are considered most important, and help to resolve or clarify disagreements. Table 3.1 provides an overview of the steps for considering the relative importance of outcomes.

Guideline developers should first consider whether particular health benefits and harms of a therapy are important to the decision regarding the optimal management strategy, or whether they are of limited importance . If the guideline panel thinks that a particular outcome is important, then it should consider whether the outcome is critical to the decision, or only important, but not critical.

To facilitate ranking of outcomes according to their importance guideline developers may choose to rate outcomes numerically on a 1 to 9 scale (7 to 9 – critical; 4 to 6 – important; 1 to 3 – of limited importance) to distinguish between importance categories.

Practically, to generate a list of relevant outcomes, one can use the following type of scales.